“The worst thing about war is not the death or torture, as repulsive as they may be… the worst thing is that it turns a man into a beast”

(excerpt from Russian documentary “Prisoners of Caucasus”)REMINDER – According to the Geneva conventions and the International Criminal Court, the widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population constitutes a war crime (crime against humanity).

Also, Russia stands accused of using internationally proscribed weapons, especially forbidden bombs.

***

(various footage of civilians during the war)

***

“The Koran and the Bible both say that if you sin, you go to hell.

We have lived through that hell already.”

Quote from ‘Anna Seven years on the frontline’ – watch below Anna Politkovskaya’s work to uncover human rights abuses in Chechnya

VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW

(source Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch)

1. Bombardment and shelling of civilian targets – despite the Russian official claims of “precision bombing” on so called terrorist targets, it was obvious that villages were attacked indiscriminately causing huge civilian casualties. The most clear proof of indiscriminate bombardment was the capital city Grozny itself, which was subjected to “carpet bombing” and was completely leveled down.

Hospital packed with wounded civilians. Towards the end of the clip – bodies of women and children who hadn’t survived. Note – throughout the war hospitals were left with no electricity, water or even basic medicine. Humanitarian help was blockaded by Russian army on Chechnya’s borders, making it even more difficult for civilians to survive.

Footage below shows what’s left after Russian shelling – house ruins and funerals. Most civilians didnt receive compensation for loss of their homes to this day

Attack in Grozny

Following the 2 wars, over 200.000 civilians and combatants were killed – most of them civilians killed during aerial bombardments. However, the Russian army denies attacking civilians and no one has been prosecuted.

2. Bombardment and shelling of refugees – related story below

Revealed: Russia’s worst war crime in Chechnya

(from british newspaper The Guardian)

Vladimir Putin is the new hero of Russian democracy, courted by Western leaders. He is also responsible for one of the most savage atrocities since the Second World War.

The village of Katyr Yurt, ‘safe’ in the Russian-occupied zone, far from the war’s front line and jam-packed with refugees, was untouched on the morning of 4 February when Russian aircraft, helicopters, fuel-air bombs and Grad missiles pulverised the village. They paused in the bombing at 3pm, shipped buses in, and allowed a white-flag convoy to leave – and then they bombed that as well, killing Taisa’s entire family and many others. (read the full story here)

3. Deployment of multiple internationally proscribed weapons

The following link shows victims in Vedeno district (children) after Russian bomb attack in 2000. The bombs used on civilian targets would not only kill, but almost pulverize a person’s body (GRAPHIC CONTENT)

http://vk.com/wall-1262161?offset=320&own=1&z=video-1262161_169179198%2Fa8588a45046d96120f

The village in which the children died

5. Purges of villages – arbitrary arrest during clean up operations, where all men aged 15-60 years old were detained for interrogation and taken to concentration camps, which are illegal by international law. According to Human Rights Watch, torture and disappearances were intrinsically related to this illegal detainment of male civilians – disappearances often times equaling murder.

Men were often detained in ground pits or other improvised spots.

6. Targeted destruction of cultural monuments, which caused incommensurable damage to Chechnya’s national legacy.

Numerous monuments had already been destroyed during Russia’s conquer of the Caucasus. Stalin and the Soviets inflicted even more harm during the deportations (when ancestral villages/monuments were blown up and history archives were destroyed in an attempt to wipe out their existence). The last 2 wars added one last drop in the destruction of Chechnya’s cultural heritage.

7. Use of torture

Photo and story by Greg Marinovich

Crowds of relatives and villagers pray and sing outside. On the porch women weep. Into the lounge, where a group of men stand around a sheet-draped body laid out on the floor. Patches of blood show through the cloth. They gently pull it off and the sickly sweet reek of decaying flesh is just a foretaste of the shocking sight. His head is formless from repeated beating that caved the skull in, his throat is slit from ear to ear and there are holes and wounds gouged out all over the torso. He had been severely tortured. He had also been castrated before death gave him relief.

◊

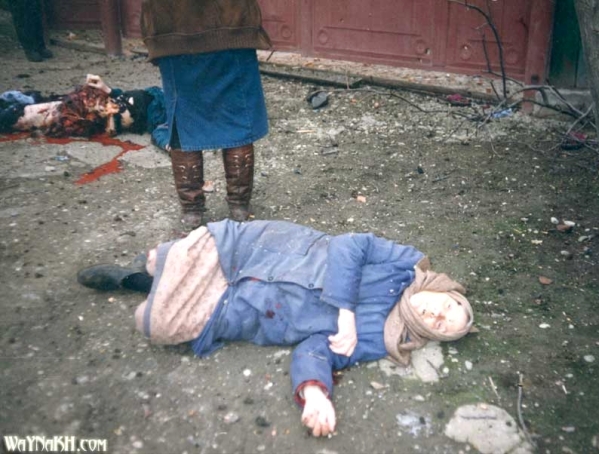

8. Murder – during raid operations, during detention.

Bodies of 2 missing men (aged 25 and 28) from Novye Atagi are found nearby after having been detained for interrogation following a Russian clean-up operation. Bodies have obvious signs of severe torture (GRAPHIC CONTENT)

The following is a Human Rights Watch report that describes how the 2 men were taken away – Human Rights Watch RUSSIA

9. Rape – on both men and women

Rape is a taboo subject in Chechen society and women are unlikely to admit to it, men are even more unlikely as it is inconceivable for them to be subjected to this kind of degradation. Rape is a common occurrence within the Russian army, especially on young conscript soldiers.

10. Trafficking – with the living (return of detainees to their families) and the dead (return of dead bodies for proper burial).

_________________________________

NOTE – among the native locals there were also Russian citizens who had been living in Chechnya for decades. They received no help or support from the Russian government to resettle in other parts of Russia (most of them had no relatives in other republics after having lived in the Caucasus for a prolonged period) and so they were left vulnerable in war-zone.

***

WAR CRIMES IN CHECHNYA

Testimony by the Emergencies Researcher at Human Rights Watch – March 2000 (end of second Chechen war)

Russia talks about fighting a war against terrorism in Chechnya, but it is Chechen civilians who have borne the brunt of the Russian offensive in this war, as in the first Chechen conflict.

Atrocities in Chechnya

Since the beginning of the conflict, Russian forces have indiscriminately and disproportionately bombed and shelled civilian objects, causing heavy civilian casualties. The Russian forces have ignored their Geneva convention obligations to focus their attacks on combatants, and appear to take few safeguards to protect civilians: It is this carpet-bombing campaign which has been responsible for the vast majority of civilian deaths in the conflict in Chechnya. The Russian forces have used powerful surface-to surface rockets on numerous occasions, causing death tolls in the hundreds in the Central Market bombing in Grozny and in many smaller towns and villages. Lately, Russian commanders have threatened to use even more powerful explosives. The bombing campaign has turned many parts of Chechnya to a wasteland.

Russian forces have often refused to create safe corridors to allow civilians to leave areas of active fighting, trapping civilians behind front lines for months. The haggard men and women who came out of Grozny after a perilous journey told me of living for months in dark, cold cellars with no water, gas or electricity and limited food.

Men especially face grave difficulties when attempting to flee areas of fighting: they are subjected to verbal taunting, extortion, theft, beatings, and arbitrary arrest. On several occasions, refugee convoys have come under intense bombardment by Russian forces, causing heavy casualties.

For many Chechens, the constant bombardment was only the beginning of the horror. Once they came into contact with Russian forces, they faced even greater dangers. Human Rights Watch has now documented three large-scale massacres by Russian forces in Chechnya. In December, Russian troops killed seventeen civilians in the village of Alkhan-Yurt while going on a looting spree, burning many of the remaining homes and raping several women. We have documented at least fifty murders, mostly of older men and women, by Russian soldiers in the Staropromyslovski district of Grozny since Russian forces took control of that district: innocent civilians shot to death in their homes and their yards. In one case, three generations of the Zubayev family were shot to death in the yard of their home.

On February 5, a few days after Secretary of State Albright met with President Putin in Moscow, Russian forces went on a killing spree in the Aldi district of Grozny, shooting at least sixty-two and possibly many more civilians who were waiting in the street and their yards for soldiers to check their documents. These were entirely preventable deaths, not unavoidable casualties of war. They were acts of murder, plain and simple. Refugees are returning to Grozny to find their relatives or neighbors shot to death in their homes.

In the past month, the Russian authorities have begun arresting large numbers of civilian men throughout Chechnya. These men, numbering well over a thousand, and some women, have been taken to undisclosed detention facilities, and their relatives are desperately trying to locate them. I have spoken to men who have been able to pay their way out of these detention facilities, and they have given me consistent testimony about constant beatings, severe torture, and even cases of rape of both men and women. One of the men suffered from a back injury after being hit with a heavy metal hammer; a second man had several broken ribs and suffered from kidney problems from the severe beatings.

The Refugee Crisis and the lack of humanitarian help

The constant attacks by Russian forces against the civilian population have caused more than two hundred thousand Chechens to flee into neighboring Ingushetia, overwhelming the local population, which numbers only some 300,000. Many more internally displaced persons are trapped inside Chechnya, especially in the southern Argun river gorge, unable to seek safety because of the refusal of Russian forces to create safe corridors.

The conditions in the refugee camps are dire, with inadequate shelter, food, clean water, heating, and other essentials. Only a minority of refugees are housed in crowded tent camps or railway cars: the majority live in makeshift shelter in abandoned farms, empty trucking containers, or similar substandard shelter; many are forced to pay large sums for private housing. Because refugees are forced to rely on their own limited resources for survival, they are often forced to return to what is still a very active war zone when they run out of money, putting their lives at renewed risk. Russia is not allowing humanitarian organizations to operate freely in Ingushetia, and is virtually blocking any direct assistance to needy persons inside Chechnya. Refugee children in Ingushetia are not attending school, and medical needs often go unmet. The contrast with the international response to last year’s Kosovo crisis is striking, although the security concerns and Russian obstruction are certainly relevant factors.

Russian authorities have repeatedly attempted to force refugees to return to Chechnya by denying them food in the camps or by rolling their train compartments back to Chechnya. Russia is attempting to relocate refugee populations to areas of northern Chechnya under Russian control, which would place them beyond the reach of international humanitarian agencies and under more direct Russian control. The border between Chechnya and Ingushetia is regularly closed, preventing refugees from fleeing to safety and often splitting up families stranded on different sides of the border. Following the destruction of the capital, Grozny, and many other towns and villages in Chechnya, and the widespread looting and burning of homes, many refugees simply no longer have a home to return to: everything they owned in this world has been destroyed.

Abuses by Chechen Fighters

Chechen fighters, particularly those among them who consider themselves Islamic fighters, have shown little regard for the safety of the civilian population, often placing their military positions in densely populated areas and refusing to leave civilian areas even when asked to do so by the local population. Village elders who tried to stop Chechen fighters from entering their villages have been shot, or severely beaten, on several occasions. In short, the Chechen fighters have added to the civilian casualty count in Chechnya by not taking the necessary precautions to protect civilian lives. There’s also evidence that some Chechen fighters have executed captured Russian soldiers.

Without minimizing the seriousness of abuses carried out by Chechen fighters, it is important to state that the primary reason for civilian suffering in Chechnya today is abuses committed against the civilian population by Russian forces.

Russia’s Failure (or refuse) to Stop Abuses

One of the most troubling aspects of the war is that the Russian authorities have failed to act to stop abuses perpetrated by their troops in Chechnya. As a result, a climate of impunity is rapidly growing in Chechnya: Russian soldiers know that they can treat Chechen civilians however they like, and will not face any consequences.

Soldiers are systematically looting civilian homes, carting away the stolen goods on their military trucks, and storing them at their barracks in plain daylight. Instead of acting to prevent abuses, the Russian military has continued to issue blanket denials about abuses. In the face of the overwhelming mountain of evidence about abuses in Chechnya, these blanket denials are unacceptable.

The Response from the West (or lack of)

Equally worrying is the lack of a strong Western response to the abuses in Chechnya. Instead of using its relationship with Russia to bring an end to the abuses in Chechnya, the Clinton administration has focused on cementing its relationship with Acting President Putin, the prime architect of the abusive campaign in Chechnya. Secretary of State Madeline Albright traveled to Moscow while bombs were raining down on Grozny, and chose to focus her remarks on Acting President Putin’s qualities as the new leader of Russia, rather than on the brutal war in Chechnya. U.S. officials continue to understate the level of atrocities in Chechnya, talking about “abuses” in the war rather than calling those abuses by their proper name, war crimes. The administration is understating the amount of influence and power it has over Moscow, because the administration wants to continue with business as usual, and mend its ties with Moscow in the wake of the NATO bombing campaign in the former Yugoslavia. To date, the international community has given the Russian government no reason to fear any repercussions for its actions in Chechnya.

War crimes tribunal

The United States and its Western allies must call the abuses in Chechnya by their proper name, war crimes, and must insist that there will be no “business as usual” with Russia while these violations continue. An immediate international monitoring presence should be established to document war crimes and other abuses in Chechnya.

The IMF and the World Bank should suspend pending loan payments until the Russian Federation takes steps to reign in its troops, begins a meaningful process of accountability for abuses, and fully cooperates with the deployment of an international monitoring presence in the north Caucasus.

Europe should bring a case to the European Court of Human Rights, charging Russia with the blatant violations of its international treaty obligations in the conduct of the Chechen war. The conduct of the Chechen war and the creation of a Commission of Inquiry should be a prominent item for discussion at the upcoming U.N. Commission on Human Rights meeting, and the U.S. must insist on a discussion of the Chechen conflict at the U.N. Security Council.

***

THE FOLLOWING ARE MEDIA AND BOOK EXTRACTS

Los Angeles Times, 17 september 2000 (full article here)

War Has No Rules for Russian Forces Fighting in Chechnya

–

“The main thing is to have them die slowly. You don’t want them to die fast, because a fast death is an easy death.”

“I remember a Chechen female sniper. We just tore her apart with two armored personnel carriers, having tied her ankles with steel cables. There was a lot of blood, but the boys needed it.”

“I would kill all the men I met during mopping-up operations. I didn’t feel sorry for them one bit.”

“It’s much easier to kill them all. It takes less time for them to die than to grow.”

—-

Troops admit committing atrocities against guerrillas and civilians. It’s part of the military culture of impunity, they say. But many now have troubled consciences. Russian officials, including the Kremlin’s war spokesman, Sergei V. Yastrzhembsky, have criticized the human rights reports, saying they are riddled with rumor and rebel propaganda. Officials have sometimes blamed reported atrocities on what they describe as rebel fighters dressed as Russian soldiers. To hear the other side of the story, a Times reporter traveled to more than half a dozen regions around Russia and interviewed more than two dozen Russian servicemen returning from the war front.

What they recounted largely matches the picture painted in the human rights reports: The men freely acknowledge that acts considered war crimes under international law not only take place but are also commonplace. In part because of Russian media coverage of Chechen slave-trading, torture and beheadings, the soldiers believe that the enemy is guilty of far worse atrocities. Although they know that executions and other human rights violations are wrong, they also consider them an unavoidable–even necessary–part of waging war, especially against such a foe.

*Before the beginning of second Chechen war, FSB (Russian Secret Services) uncovered a tape which recorded the killing of 4 captured Russian servicemen in 1996 near Komsomolskoye. Three were shot in the head, the fourth had his throat cut and was beheaded on tape. The tape was shown to human rights organizations across Europe and it was replayed over and over again on Russian television. The Chechen perpetrators were caught and/or killed. The leader of the group said he acted “in revenge” for the rape and murder of his cousin by Russian forces. He was sentenced to life in prison.*

Moreover, after a series of bomb attacks in Russia that killed more than 300 people, the Russian public and Russian servicemen have accepted the official line that this is not a war against unsavory separatists but a fight against inhuman “bandits and terrorists.” The Russian apartment bombings of 1999 were instantly blamed on Chechen perpetrators though no proof was officially presented. The result of the official report was sealed. An unsettling possibility emerged from unanswered questions, and an FSB agent publicly accused the Russian authorities – for more info read here.*

The view has been enhanced by a barrage of news reports depicting the fighters as mercenaries and religious fanatics, many of them from other countries. While it’s unclear what proportion of the fighters come from outside Russia, many of the servicemen were convinced that it was a majority–making it easier to consider them alien.

“What rules? What Geneva Conventions? What difference does it make if Russia has signed them?” said a 25-year-old army officer. “I didn’t sign them, none of my friends signed them. . . . In Russia, these rules don’t work.”

——————-

“The main thing is to have them die slowly. You don’t want them to die fast, because a fast death is an easy death.” —

Andrei Andrei’s pale eyes glow against his tanned skin. He’s been home only 10 days. He opens and closes kitchen cabinets, searching confusedly for sugar for his tea. “I still haven’t gotten used to domestic life,” he apologizes. He has just turned 21. During basic training, he recalls, Red Cross workers came to his base to teach about human rights and the rules of war. “They tried to teach us all kinds of nonsense, like that you should treat civilians ‘politely,’ ” he says. “If you behave ‘politely’ during wartime, I promise you, nothing good will come of it. I don’t know about other wars, but in Chechnya, if they don’t understand what you say, you have to beat it into them. You need the civilians to fear you. There’s no other way.” Andrei says the lesson that stuck was the one his commander taught him: how to kill. “We caught one guy–he had a fold-up [radio] antenna. He gave us a name, but when we beat him he gave us a different name. We found maps in his pockets, and hashish. He tried to tell us he was looking for food for his mother. My commander said, ‘Stick around and I’ll teach you how to deal with these guys.’ He took the antenna and began to hit him with it. You could tell by the look in [the Chechen’s] eyes that he knew we were going to kill him. “We shot him. There were five of us who shot him. We dumped his body in the river. The river was full of bodies. Ours, too. Three of our guys washed up without heads.” Andrei says he knows that officially, Russian troops are supposed to turn all suspected rebels over to military procurators. But in practice, his unit literally took no prisoners. “Once they have a bruise, they’re already as good as dead,” Andrei says. “They know they won’t make it to the procurator’s office. You can see it in their eyes. They never tell us anything, but then again, we never ask. We do it out of spite, because if they can torture our soldiers, why shouldn’t we torture them?” “The easiest way is to heat your bayonet over charcoal, and when it’s red-hot, to put it on their bodies, or stab them slowly. You need to make sure they feel as much pain as possible. The main thing is to have them die slowly. You don’t want them to die fast, because a fast death is an easy death. They should get the full treatment. They should get what they deserve. On one hand it looks like an atrocity, but on the other hand, it’s easy to get used to. “I killed about nine people this way. I remember all of them”, says Andrei.

(warning! some scenes contain extreme physical abuse)

——————-

“It’s much easier to kill them all. It takes less time for them to die than to grow.” –Valery

Valery is a personnel officer, what in Soviet times would have been called a commissar. He’s a lieutenant colonel responsible for morale and discipline. He shouldn’t talk to reporters. But the night is dark, the beer from the roadside kiosk outside his army base is cold, and he has a lot on his mind. He checks documents, then launches into a diatribe. “In this war, the attitude toward the Chechens is much harsher. All of us are sick and tired of waging a war without results,” he says. “How long can you keep making a fuss over their national pride and traditions? The military has realized that Chechens cannot be re-educated. Fighting against Russians is in their blood. They have robbed, killed and stolen our cattle for all their lives. They simply don’t know how to do anything else. . . . “We shouldn’t have given them time to prepare for the war,” he continues. “We should have slaughtered all Chechens over 5 years old and sent all the children that could still be re-educated to reservations with barbed wire and guards at the corners. . . But where would you find teachers willing to sacrifice their lives to re-educate these wolf cubs? There are no such people. Therefore, it’s much easier to kill them all. It takes less time for them to die than to grow.” Valery was in Chechnya in the early phase of the war, when he says there was little oversight from the high command and there were no pesky journalists.

“Now the press sets up a howl after the death of every Chechen. It has become impossible to work. We know very well that thousands of eyes are watching us closely. How are we expected to fight the bandits in such circumstances? “The solution, in fact, would have been very easy–the old methods used by Russian troops in the Caucasus in the 19th century. For the death of every soldier, an entire village was burned to ashes. For the death of every officer, two villages would be wiped out. This is the only way this war can be brought to a victorious end and this rogue nation conquered.”

French writer Alexandre Dumas recounted after a trip to Caucasus how Russian army soldiers invited him to go “hunting locals”.

Valery acknowledges that atrocities occur but says that, in effect, soldiers are carrying out a policy the government needs but is afraid to declare.

“For political reasons, it’s impossible to murder the entire adult population and send the children to reservations,” he says. “But sometimes, one can try to approximate the goal.”

——————-

Mop-up operation captures abuse on teenage boy. During and after the war, all boys over 15 (of “fighting age”) were systematically taken to filtration camps.

Also, the parents of murdered girl picked up by Russian troops speak up

–

DOING THE JOB RIGHT

Russia has deployed a motley force of 100,000 in Chechnya. Among them are elite police commandos, known as OMON and SOBR, as well as enlisted Interior Ministry troops consisting of both conscripts and contract soldiers. Russia’s first war in Chechnya was largely–and badly–fought by conscripts. By law, all Russian men are supposed to serve for two years starting at age 18, and in the previous war many found themselves in the war zone before they knew how to fire their rifles. This war was supposed to be different, to be fought mostly by second-year conscripts and professional soldiers. But contract soldiers, while older, are not really professional. They are largely men who sign up for the money.

“I signed up because I have nothing else to do,” said one, who admitted that he had just split up with his wife and has been unable to find a regular job. “If things were normal here, I wouldn’t go, but the way things are, what other choice do I have?”

The elite police forces, while highly trained, also are not exactly combat soldiers. The OMON is largely schooled in riot and crowd control, SOBR in fighting organized crime. The police special forces tend to be older, and most have families. If they refuse an assignment in Chechnya, they face discipline or dishonor. So, many take the assignments and do whatever it takes to return home safely. To induce the contract soldiers to sign up, the Russian government offers hefty combat pay–800 rubles a day, about $28. At home, career soldiers and police earn only about 1,500 rubles, about $50, in an entire month. While the career soldiers and elite police forces face professional pressure to serve in Chechnya, contract soldiers are volunteers, viewed with suspicion by many of the other branches as little more than mercenaries.

“The worst thing is when a person goes to Chechnya to make money,” said a 34-year-old OMON officer. “A person who does that should really have his head examined by a psychiatrist, for this person clearly has a propensity for sadism.”

——————-

FEARING ONLY FEAR

Most of the interviewed servicemen describe a corrosive atmosphere of fear and isolation in the war zone that was often relieved by acts of violence against Chechens, both fighters and civilians. Such fear was compounded by the difficulty of coordinating between Defense and Interior Ministry forces; soldiers reported frequent misunderstandings, including an unnerving number of casualties from “friendly fire.”

“You can’t imagine anything more horrible than the sight of your buddy, who was at your side a few minutes ago, blown to pieces, bits of his flesh steaming in the snow,” said one 19-year-old conscript. “Especially when it’s your own side that did it.”

As a result, many Russian units feel vulnerable and isolated on the battlefield. They aren’t sure that they can count on other units to keep them supplied and safe. One theme repeated by many is that in the war zone, each unit’s commander was left to set his own standards. “I was lucky I wound up in a good regiment that wasn’t a madhouse, with a normal commander,” said the 35-year-old soldier. “Everything depends on the commander.” Moreover, most of the servicemen had been told that the Chechens had a special animosity for their particular unit–that they would suffer excruciating torture at Chechen hands if they had the misfortune to be captured. True or not, those stories induced many Russian servicemen to assume the worst about any Chechen they met–man, woman, young, old. “Our commander told us all the time, ‘There’s no such thing as a Chechen civilian,’ ” a conscript said. Finally, the servicemen said they resort to atrocities because the authorities–both the political leadership and the judicial system–leave them unprotected.

“Bespredel emerges when soldiers know that the state is too far away or too little interested in supporting or controlling servicemen,” said one 25-year-old police commando. “And then everyone starts acting on his own, making his own decisions on the spot. Everyone is responsible for his own life. How decently he does that depends on his individual experiences, both good and bad, and on his level of cynicism.”

In his book, a Russian veteran describes the abuse suffered by young soldiers in the Russian army, and also showcases the chaos and lack of organization withing the system One Soldier’s War in Chechnya.

Daily Mail related article here “My descent into Hell”

——————-

FIGHTING “TOTAL WAR”

The Soviet Union signed the Geneva Conventions after the end of World War II. Officially, that means that Russia’s armed forces are obligated to abide by the principles of the accord: that civilians and combatants who have surrendered should be treated humanely and that violence of any sort or execution of war prisoners is forbidden. The Russian armed forces have a few cultural features that make wartime atrocities more likely than in Western armies. “Russians come from a tradition that all war is ‘total war,’ said Jacob Kipp, professor at the University of Kansas and an expert on the Russian army. “After you’ve made the decision that it’s right to start a war, there isn’t any notion that there can and should be limits on how you conduct the war.” Second, the Soviet army tolerated a higher level of casualties than Western armies, a mind-set that continues. Some servicemen said they were convinced that their commanders considered them expendable.

“In Russia, winning wars has always been a matter of quantity, not quality,” said one conscript. “They don’t even count us as losses. We’re just meat. A conscript is nothing in the army. It’s like a chain–the generals don’t value our lives, so we don’t value the lives of the Chechens.”

***

–

Third, the Russian public has been in favor of the war. *Before the beginning of second Chechen war, the public was resentful of another conflict. The Russian apartment bombings and the FSB dig out of murdered Russian soldiers tapes have changed the general opinion in favor of war* In such a climate, the subject of atrocities committed by the Russian side is all but taboo in Russian society. Finally, the Russian armed forces–unlike Western armies–have no effective system of accountability for wartime conduct. Not only do the authorities not make a serious effort to investigate war zone misconduct, but they also go further. The 23-year-old army officer recounted how investigators from the military procurator’s office and the Federal Security Service, or FSB, helped his unit cover up war crimes such as the summary execution of detainees.

“The FSB officers would always write in their reports: ‘Killed in cross-fire,’ ” he said. “They would never give away our soldiers. There’s always been mutual understanding. It’s the same as if your son kills a bandit–would you go and report him to the police? Of course not. The same with the FSB. They were on our side. They understood us and supported us.”

The military procurator’s office, which operates today much as it did in Soviet times, tends to focus on misconduct within the ranks–offenses such as hazing and selling service weapons–not the treatment of civilians and enemy fighters. The chief spokesman for the general procurator’s office, Leonid Troshin, said he couldn’t say how many of the servicemen have been charged with serious crimes or crimes against civilians, or whether any of them had been convicted.

“The number of crimes committed by [rebel] fighters by far surpasses the number of crimes committed by Russian servicemen,” Troshin said. “This is exactly what we have been trying to prove.”

” There are many people even among the military who say this must end,” Aslakhanov said. “But it is like dirty laundry that they don’t want to air in public.” Russian servicemen warn that the large amount of bespredel on the Russian side is not only harming Chechens, it’s also creating a new generation of troubled Russian men with deep psychological problems, many of whom are violent. Many of the returning servicemen said they were experiencing symptoms such as nightmares and an inability to control their anger. Many said they or their comrades were drinking heavily.

◊

Excerpts from Emily Gillian’s book “Terror in Chechnya: Russia and the tragedy of civilians in war”

Chernokozovo detention center – the infamous “filtration camps”

Russian journalist Andrei Babitski (detained for 2 weeks at Chernokozovo for filming the war in Grozny “without authorization”): “In my view, it differed very little from a Nazi or Stalinist concentration camp”

The filtration point marked the creation of Russia’s own “spaces of exception” in its war. Originally established on the basis of the Ministry of the Interior Directive No. 247 of 1994, the unofficial detention points had no legal basis in Russian law. As the Russian government continued to argue that what was taking place in Chechnya was not an internal armed conflict but an “antiterrorist operation”, it was nevertheless bound by the legal provisions of the Russian Criminal Code and the Russian Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment – all of which banned arbitrary detention and torture.

“Filtration” had two formal objectives. The first was to filter out the suspected fighters from civilians. It was therefore inevitable and even expected that civilians would be part of this process. The second objective was to filter the fighters out in order to transfer them to pre-trial detention centers. Far ever-increasing number of civilians were also swept up in this arbitrary process – men and women. The filtration points were never subject to normal due process between 1999 and 2005, and the Russian armed forces defied any attempt to regulate their existence. As one member of the Russian Special Forces confessed: “The only way to struggle against lawlessness is with lawless ways”.

The fundamental issue, however tested not only with the existence of the filtration points, but with the treatment of those detained within them. Allegations of torture and of cruel and inhumane treatment at the pre-trial detention center Chernolcozovo first reached the international news circuit via an article in french newspaper Le Monde on February 4, 2000. While on the border of lngushetia at checkpoint – Sophie Shihab, a French journalist, was passed a letter by a Chechen. Allegedly written by a Russian guard serving at Chernokozovo, where an estimated 750 detainees were being kept, the letter explained:

“I cannot describe the exotic methods being used to break the human spirit, turning a human into an animal. I finish writing this trifle, but if on this earth there is some force, help these people. l am disappointed in my government, its lies, cunning and duplicity.”

Minute 35:36 – bodies of torture victims, wounds described in detail

–

The facts outlined in the appeal are impossible to dispute – as they were fully supported by other testimonies, including that of the well-known Russian journalist Andrei Babitki, who was detained in Chernokozovo from January 16 to February 2, and of tortured detainees who crossed the border into lngushetia in the middle of February. It later grew clear that Chernokozovo had once been a correctional facility, and although in a state of disrepair – it was being used, according to government sources, as a “reception and identification center” by Russian troops at the time of the second war. It is impossible to determine which divisions served in the facility and perpetrated the abuse. Fearing identification and possible future retribution, Russian soldiers in Chechnya frequently wore camouflage uniforms with no division patches or pins that could identify them. However, six interviewees testified that the Rostov UMUN supplied the guards and commanded the facility during this period before it was handed back to the Ministry of justice in February.

One detainee recalled: “They took us to the camp Chernokozovo. About 50 soldiers in camouflage uniform, in masks and with truncheons in their hands met us. They quickly dispersed to form a corridor which they forced us to go through. As soon as we stepped into line, blows from the truncheons started falling on our backs, heads and other parts of the body. . . It turns out that on this first day I had several broken ribs. Then they took us into a separate space and ordered us to undress. The corporal punishment continued. They beat all of us; some be- cause they screamed out, others for silently tolerating the blows.” The human corridor cynically framed what awaited the detainees inside Chernokozovo. Prepared to inflict severe pain and suffering to obtain in- formation or forced confessions. the Russian troops’ desire for signed confessions appeared important. But not necessarily paramount.

“They tried to make me sign confessions that we were wahhabis, fighters, or that we were supporting the fighters. I did not sign,” recalls one detainee. “They used electric shock to make me sign. but I did not do it. I was forced to put my back to the wall. . . There were two cables. and they held the cables to my body. . . They splashed water in my face. Two or three times during the interrogation, they electrocuted me.”

The rituals included forcing detainees to crawl on the ground:

“They ordered me to crawl along the corridor, which was twenty meters long. I tried to crawl and one of the soldiers was kicking me in the kidney and another in the shoulder.’They would make us say ‘Comrade Colonel. let me crawl to you.’ . . After that, they beat us. They made us say thank you.”

Genital beatings or electroshock was inflicted to force confessions. But testimonies also suggest an intent to inflict irrevocable damage to reproductive organs: “You will leave here half a man. . . Do you want to have children? “

“It was February, late at night. I was lying on the floor, two guards held my legs while another kicked me in the testicles. . . They would beat me unconscious and wait until I came round, woken up and they would come in and beat me again.”

Two witnesses spoke of being physically branded at Chernokozovo. The threat of marking foreheads with green iodine was first heard of in Novye Aldi. Victims detained during the sweep in the village of Shami Iurt in February we’re taken to Tolstoi-Iurt. During transportation, a Russian soldier warned Dashaev and another man named Viskhanm that if their noses were marked in red, they were being branded for summary execution. He cautioned that it would be better if they were covered in green iodine. But both Dashaev and Viskhan were later covered in green iodine and released. The full extent of this practice remains unclear. The Russian government rejected the reports of torture at Chernokozovo. The deputy minister of justice, Colonel General Yuri Kalinin, concluded: “The accusation that the detained are being tortured and beaten is just sheer lies and slander.” Valerii Kraev, first deputy head of the Ministry of ]ustice’s Corrections Department, said: “All the isolators existing in Chechnya operate in complete observance of all the international conventions.”

Sophie Shihab talks about the Chernokozovo letter (at 31:00)

“The screams of men who have been broken in every conceivable way”

◊

In the video below, Russian journalist Babitski describes his experience at Chernokozovo filtration camp. Also contains testimony of a detainee of the Temporary Police Prison in Grozny (later deemed illegal)

Scrawlings found on the walls of the cellars “Where am I? What is happening to me? Am I alive or not? March 27 2006”

“Everything passes. This too will pass”

——————————–

Excerpts from Emily Gillian’s book “Terror in Chechnya”

Novye Aldi massacre

Local civilians had begun to flee Novye Aldi on the southern outskirts of Grozny once the bombing of the capital began on September 22, 1999. News of long lines of IUPs waiting to enter neighboring Ingushetia, the closure of checkpoint”Kazkaz 1,”and the tragic firing on a Red Cross convoy on October 29 however, convinced many to stay. In the same way that the civilians of Gekhi and Staraia Sunzha sought to protect their communities from both sides of the conflict, about one hundred locals approached the Russian position on February 3. Under the protection of a white flag, they sought to assure the Russian troops that the separatist forces had left the village.” As they approached the Russian position, the locals were fired upon. A Russian civilian from neighboring Chernorech’e was shot. The crowd was ordered to lie face down on the ground. The young man died before the crowd was permitted to stand up. The locals nevertheless met with Colonel Lulcashev, commander of the 15th Motor Rifle Regiment. They asked him to stop the strikes and the dropping of cluster bombs, insisting that there were no Chechen fighters in the village. “We explained that there were no fighters in the town, that it was safe to go in. ‘If you don’t take our word for it,’ we said, ‘you can detain us as hostages; or we tan walk in front of you as human shields.” Colonel Lukashev promised to stop the bombing. “He said he would stop the artillery,” recalled Aset Chadaeva, a pediatric nurse, “but not the bombs-orders to drop bombs were always given the clay before”.

The bombing ceased the next day. On February 4. Families began to emerge from their cellars, anxious to return home, hopeful that the bombing had ceased. On the evening of February 4, 2000, poorly dressed and exhausted Russian conscript soldiers entered Novye Aldi, walking around the streets in groups of five and ten, checking passports, they warned the civilian population of a sweep operation planned for the following clay. “We talked to them, offered them food. whatever there was . . . they warned us that the ‘bloodhounds’ would be sent in later,” recalled Marina Ismailova. “ Some soldiers were rude, others polite. But there were no killings or violence.“

Aset Chadaeva recalled the soldiers telling her: “Don’t stay inside.” “Don’t stay in the basement’ one of them said to me, ‘they will unleash the dogs on you.’’ “Don’t stay in your cellars, contract soldiers will come and throw grenades in,” Raisa Soltalthanoya, a 39-year-old cook, remembered the soldiers saying.” Novye Aldi was surrounded by armored personnel carriers (APCs) on the morning of February 5. Pollution from the burning factories of the surrounding Grozny chemical plant and burning oil wells blackened the sky.

That morning, a resident recalled, “two soldiers were running down the road shouting warnings that contract soldiers were coming. They shouted: If you have fighters, hide them. If you have young women, hide them or they will be raped.” I then saw contract soldiers coming with bandanas on their heads.” Snipers surrounded the village. and an estimated 100 soldiers entered Novye Aldi around 9 am. Some were privately contracted soldiers, while others were members of the MVD Special Forces and St. Petersburg and Ryzan OMUN forces. According to one witness testimony, the soldiers told him that they were from the 2-15th Motorized Rifle Regiment, 6st Company.

It appears that the younger conscript soldiers were responsible For cordoning off the area, and the Special Forces and contract soldiers conducted the sweep. They walked around in groups of seven to ten. Chadaeva recalled that two of the men in the groups were always well dressed and clean shaven; some of the men were in uniform and others were in civilian clothes. “They looked like official men. FSB. . . The others wore camouflage pants, some with white T-shirts, others with tattoos and no shirts, even in that cold weather. One had a fur hat with a fox tail. They had no military identification or insignias.”

Chadaeva further recalled, “My father and I went out into the street and saw the soldiers setting houses on fire. Our neighbor was repairing the roof of his house and a Russian soldier took a gun and wanted to fire at him. I shouted, ‘Don’t shoot. He is deaf!’ . . . The first words we heard from them when they saw us were “Mark their foreheads with green iodine so that we’ll have a better target to aim at.”

One of the soldiers pointed a gun at Chadaeva’s chest and shoved her against a metal gate. The officer in charge told the soldier “to leave me alone,” she recalled. “He [the officer] told me to stay close to him and shut my mouth. And then he asked me how many people there were in Aldi. ‘Thousands,’ I say. ‘What?’ he says.What are you doing, bitch? Why don’t you get out of here?’ He was trying to avoid eye contact. He was shaking. He told Chadaeva: “We have orders not to let a mouse escape from here.”

The officer allowed Chadaeva to gather her neighbors on the corner of Chetvertoi Almaznyi lane and Kamskaia Street for a passport check. She urged the residents of her street and the intersecting lanes to gather together on the corner. “I thought that if they [the Russian troops] saw that there were children, all of us together.” she recalled, “then perhaps they wouldn’t do anything to us. ” The soldiers were pushing people into their homes, throwing grenades into basements full of civilians, and setting houses alight with people inside.

Read the outcome of the Novye Aldi mopping-up (zachistka) operation here

Documentary shot by Natalya Estemirova, Russian human rights activists who was murdered in 2009 in Grozny

◊

Atrocities in Chechnya Breed Despair, Anger

(the following are excerpts; read full article here http://articles.latimes.com/1995-02-19/news/mn-33895_1_russian-soldiers)

February 19, 1995 AVTORI, Russia — For no particular crime, Russian soldiers beat Uvayes Batalov every day for nearly a month. They starved him, jolted him with electricity and locked him for days with other prisoners in a specially overheated railroad car with little water. “The guards came to the door and said, ‘Do you want some fresh air?’ ” recalled Batalov, a 26-year-old Chechen construction worker who was unarmed at the time of his arrest. “We said, ‘We do, yes!’ So they came in and beat us with clubs. Later they came back. They said, ‘How about some fresh air?’ We said, ‘No, no!’ But they came in and beat us anyway.”

“The guards came to the door and said, ‘Do you want some fresh air?’ ” recalled Batalov, a 26-year-old Chechen construction worker who was unarmed at the time of his arrest. “We said, ‘We do, yes!’ So they came in and beat us with clubs. Later they came back. They said, ‘How about some fresh air?’ We said, ‘No, no!’ But they came in and beat us anyway.”

Teenage army conscripts pile onto tanks in groups of 10 or more and race through Grozny’s streets, shouting drunken obscenities at passersby and shooting wildly.

“The city is swimming in alcohol,” said Boris Polovinkin, a Moscow police captain brought to Grozny to help restore order.

“There’s nothing to feed the troops with,” he said in an interview. “So the government riles them and turns them loose, (saying,) ‘Go, take what you want.’ ”

Human rights monitors say many prisoners are routinely tortured in an effort to extract confessions, while others are not questioned at all but apparently beaten out of vengeance.

“The Russian army has not captured a single Chechen fighter. They’ve only captured civilians,” said Anatoly Y. Shabad, a member of the Russian Parliament who spent a week in Chechnya documenting cases like Batalov’s.

Batalov and his father were freed Jan. 26 in a prisoner exchange–48 Chechen civilians for 47 Russian paratroopers.

“When those paratroopers walked past us and saw the shape we were in, there were tears in their eyes,” Batalov said. “Before, I was a peaceful citizen, but now I’m going to become a moujahedeen. As long as that’s what they called me, let it come true.”

Read full article here http://articles.latimes.com/1995-02-19/news/mn-33895_1_russian-soldiers

◊

Chechen Refugees Describe Atrocities by Russian Troops

Washington Post – June 29, 2002

NAZRAN, Russia — Kuslum Savnykaevna has no intention of hearing the Russian government’s wish that she abandon the converted car repair shop where she and her five children live in Ingushetia and return to their former home in neighboring Chechnya. And if she ever had any doubt that they must remain refugees in this impoverished region in southern Russia, she said, what she witnessed in the last month erased it. In mid-May, Savnykaevna went to visit her parents in Mesker Yurt, a village of roughly 2,000 about seven miles east of Grozny. She had not been there long when Russian troops suddenly surrounded and closed off the village to conduct a zachistka, or cleansing operation, that lasted three weeks. She said she saw some of the victims of the operation after their relatives carried them back from a field the soldiers had occupied at the edge of the village: a man whose eye was gouged out; another whose fingers were cut off; a third whose back had been sliced in rows with the sharp edge of broken glass, then doused with alcohol and set afire, according to his relatives. Her brothers and nephews were spared, she said, only because her family paid the soldiers a $400 bribe not to hurt them. Russia’s military commander in Chechnya, Col. Gen. Vladimir Moltenskoi, told the Defense Ministry newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda earlier this month that the mop-up operation was conducted properly and found a large cache of weapons and evidence of a school for rebel snipers. “Mesker Yurt is a pro-bandit village. A group of at least 50 fighters was active here,” he said. A Russian colonel in Grozny told Russian Tass, the semi-official news agency, that soldiers killed 14 rebels who put up armed resistance during the zachistka.

In interviews last week, residents and visitors who were trapped in Mesker Yurt described what took place in the 21 days that the village was shut off from the outside world.

The trouble in Mesker Yurt started on May 18 when a group of men abducted a 36-year-old Chechen named Sinbarigov, who some villagers said worked for Russia’s Federal Security Service. The next day, his head was found on a stick next to the village administration building, according to Memorial. The Chechen rebels’ Web site said the man was executed because he had helped the Russian authorities. The following day, Russian troops circled the village and blocked the roads with armored vehicles. Savnykaevna, the Ingushetia refugee, said residents decided their only defense was to send every male resident from the ages of 13 to 35 to the red brick mosque in the center of the village. She said 200 to 300 men fled there. She and the women of the village surrounded it, trading places when they grew tired of standing in front of the soldiers’ pointed guns. After three days, she said, the men went back to their houses, because the soldiers threatened to blow up the mosque. “Then on the fourth day, after lunch, they started arresting, killing, torturing,” she said. More than a dozen soldiers rushed into her parents’ house, she said, and slipped black masks over the heads of her three brother and her nephew. They demanded 12,000 rubles — about $400 — to let them go, she said. Other men were dragged off to the field where the soldiers had camped and were tortured, villagers said. When the streets were clear of soldiers, Savnykaevna said, she visited the homes of her parents’ neighbors. Three brothers from one family were arrested, she said. “They brought back only a bag with their bones inside,” she said.

A worker from the Russian-Chechen Friendship Society, who visited the village, identified the brothers as Apti, Adam and Abu Didishev. In another house, Savnykaevna said, two brothers lay in bed, one with an eye plucked out, the other with four fingers of one hand missing. She said his parents told her both had been tortured with electricity, leaving dark marks on their faces and arms. She said she saw soldiers beating the bare feet of one man with an iron pipe while the man’s legs dangled outside the opening of a tank. Later, when she visited his home, she said his relatives told her the soldiers had sliced his back with broken glass, rubbed salt in his wounds, then doused his back with alcohol and burned him. The family of Said Abubakarov, 19, found his shirt with his fingers in the pocket, according to the account provided to the Russian-Chechen Friendship Society.

Word leaked to Moscow, where angry Chechens filled the office of Aslakhanov, the Duma deputy. He flew to Ingushetia and drove to Mesker Yurt on June 9, the day before the Russian troops left. With him was a civilian prosecutor and military prosecutor assigned to Chechnya. At the village, he said, he found representatives of numerous Russian military and law enforcement agencies. They refused to let them enter the village, he said, telling him it was too dangerous. Asmalika Ejieva, 41, said the soldiers told the villagers to show up at the field at 8 the next morning and their relatives would be released.

The next morning, the field was deserted, she said. In freshly dug pits, she said, they found parts of bodies that appeared to have been blown up with explosives. Ejieva said people are terrified that if they describe the horror, they will be killed. Some are leaving for the relative safety of Ingushetia, she said, because the Russians left with a promise: In 10 days, they would come back.

◊

Doctor Khassan Baiev, “The Oath: A Surgeon Under Fire” extract from his book about the Chechen wars

“Dozens of charred corpses of women and children lay in the courtyard of the mosque, which had been destroyed. The first thing my eye fell on was the burned body of a baby, lying in fetal position… A wild-eyed woman emerged from a burned-out house holding a dead baby. Trucks with bodies piled in the back rolled through the streets on the way to the cemetery. While treating the wounded, I heard stories of young men – gagged and trussed up – dragged with chains behind personnel carriers. I heard of Russian aviators who threw Chechen prisoners, screaming, out their helicopters.

There were rapes, but it was hard to know how many because women were too ashamed to report them. One girl was raped in front of her father. I heard of one case in which the mercenaries grabbed a newborn baby, threw it among each other like a ball, then shot it dead in the air. Leaving the village for the hospital in Grozny, I passed a Russian armored personnel carrier with the word SAMASHKI written on its side in bold, black letters. I looked in my rearview mirror and to my horror saw a human skull mounted on the front of the vehicle. The bones were white; someone must have boiled the skull to remove the flesh.”

*Rapes on both men and women were common, however they are under-reported as “rape” is a big taboo in Chechen society and neither men nor women would admit it*

Ruslan Gelayev, Chechen commander: “It is hard to understand where the people are coming from who are capable of digging in a live human body for hours when conducting tortures. We are discovering bodies with insides torn out, with eyes plucked out, with heads scalped, with tongues cut off – and often all of these are traces of tortures are left on one dead body. I will never forget a tin bucket found where Russians were staying. There was a boiled human head in it. A lot of things I just can’t say. “

◊

Grozny, Chechnya. January 10, 1995. Children taking shelter in a basement fall victims to bombardments

◊

◊

January 2001 – Civilians of Novye Atagi after a Russian sweep operation (with visible signs of severe torture). Other Novye Atagi men “disappeared” and were never found

◊

Children victims after a military assault

WARNING! EXTREMELY GRAPHIC! Watch at your own risk

◊

“Chechnya: The Final Solution”

An exhibition of 300 pictures with name of ”Chechnya: The Final Solution” took place in Poland, Czech republic and Denmark in 2007. The photos displayed wounded, tortured and killed civilians in pictures taken by various war photographers. The organizers tried to hold the exhibit at the European Parliament in Brussels last year but officials prevented it from appearing after declaring that some of the pictures were “repulsive.” That is the exactly the point – it is repulsive. But then again they did not bother with this repulsive reality for 20 years, why would they bother now?

***

Pingback: Tactics and War crimes of Russian Army in Caucasus - Historum - History Forums